About PNH

Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH) is characterized by hemolysis, thrombosis, and bone marrow failure

PNH is a rare, acquired clonal disorder of hematopoietic stem cells caused by a somatic mutation in the PIG-A gene, leading to the production of red blood cells with absent or decreased expression of GPI-anchored proteins, including CD55 and CD591-3

In the absence of CD55 and CD59, RBCs become susceptible to complement mediated-hemolysis2

Hemolysis can be intravascular or extravascular. IVH occurs inside the blood vessels, while EVH occurs in the liver and spleen2

IVH occurs when PNH RBCs are destroyed by the membrane attack complex (MAC) in the terminal complement pathway2,4

EVH occurs when C3 fragments get deposited on PNH RBCs, tagging them for removal and destruction by macrophages in the liver or spleen in the proximal pathway of the complement system2,4

Those living with PNH can struggle with the effects of uncontrolled or poorly controlled hemolysis1

Patients with PNH face IVH and may develop EVH.

*Based on preliminary studies in patients treated with eculizumab suggesting terminal complement inhibition induces C3 fragment deposition on PNH RBCs. The C3 fragments trigger destruction of the RBCs by macrophages, making EVH a potential consequence of terminal complement inhibition. Additional studies are needed to further understand the impact of terminal complement inhibition on EVH.2,4,5,7-11

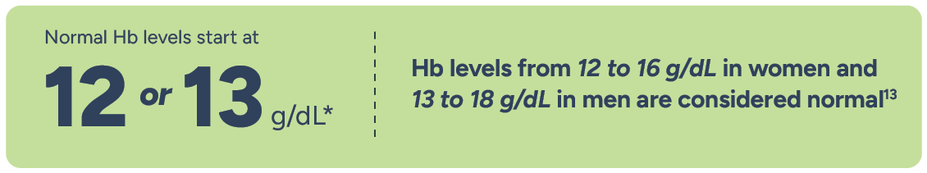

It may be time to aim for higher Hb levels when treating patients with PNH

Uncontrolled or poorly controlled hemolysis can cause adults with PNH to experience below-normal Hb levels12

*Normal Hb levels vary but generally are 12-16 g/dL for women and 13-18 g/dL for men.13

Data from a cross-sectional US survey of adults with self-reported diagnoses of PNH (N=122) evaluated the relationship between exposure to terminal complement inhibitors (eculizumab: n=35; ravulizumab: n=87) and clinical parameters, PNH symptoms, quality-of-life outcomes, and FACIT-Fatigue scores. Most patients (96.7%; eculizumab: n=35; ravulizumab: n=83) were on a C5i for ≥3 months. History of aplastic anemia was reported in 33.6% (41/122) of patients. Other comorbidities, such as myelodysplastic syndrome and other bone marrow disorders, were reported by <6% (n=7/122) of patients. Hb data were analyzed for respondents with PNH who reported Hb levels (n=114). Transfusion data are from survey respondents who had received at least 1 year of C5i treatment and who had experienced at least 1 transfusion in their lifetimes (n=54).2

Potential study limitations include2:

The sample size for this survey is small, given PNH is a rare disease

The survey could be subject to selection bias, where dissatisfied patients are more motivated to participate

Subjectivity of patient-reported outcomes

Despite C5 inhibition, some patients with PNH may remain fatigued or require RBC transfusions

For undiagnosed patients, your diagnosis of PNH can make a difference

PNH is a rare, acquired clonal disorder characterized by hemolysis, thrombosis, and bone marrow failure (BMF).1,14

Could there be patients in your practice with undiagnosed PNH? Learn more from the Diagnostic Tool on the Resources page.

Variable clinical presentation of PNH may contribute to diagnostic delays12,14

Patients reported significant diagnostic delays in one study that surveyed 163 adults with PNH12,16: | |

24% of patients were diagnosed after >5 years | ~38% of patients saw ≥5 HCPs prior to PNH diagnosis |

Patients living with undiagnosed PNH may face RBC transfusions, thrombosis, and other major vascular events.12,15

Your diagnosis is essential because similar symptoms can require vastly different treatments14,17,18

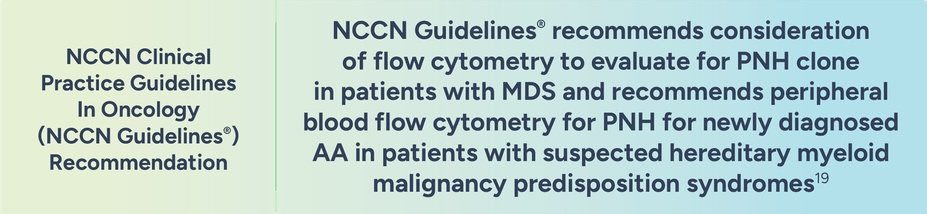

PNH symptoms often overlap with those of aplastic anemia (AA) and myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS), as these diseases can be associated with each other

PNH is not mutually exclusive to BMF disorders

The NCCN makes no warranties of any kind whatsoever regarding their content, use, or application and disclaims any responsibility for their application or use in any way.

Could a different treatment approach help patients with PNH achieve normal Hb levels of 12 or 13 g/dL?